The release of fifteen American civilians from Iraq in November 1990, facilitated in part by Muhammad Ali, represents a distinctive episode in the diplomatic history of the Gulf Crisis. Occurring in the months between Iraq’s invasion of Kuwait and the outbreak of full-scale war, the event illustrates how informal humanitarian interventions could momentarily intersect with rigid state-centered power structures. While the episode did not alter the course of the Gulf War, it remains historically significant as a rare instance in which a private individual exercised influence within a frozen diplomatic environment.

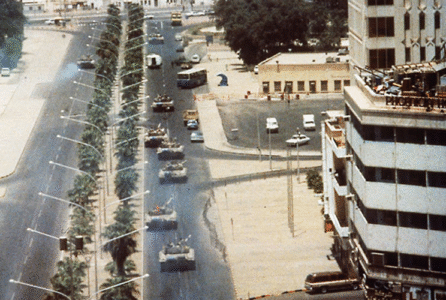

On 2 August 1990, Iraqi forces invaded Kuwait, rapidly occupying the country and declaring it Iraq’s nineteenth province. The invasion triggered swift international condemnation and led to the imposition of economic sanctions under United Nations Security Council Resolution 661. The United States, alongside allies, began assembling a military coalition in the Persian Gulf under the framework of Operation Desert Shield.

In the weeks following the invasion, Iraq restricted the departure of foreign nationals from coalition countries. By late August, hundreds of Western civilians were prevented from leaving Iraq or Kuwait. Iraqi officials initially described these individuals as “guests,” but their strategic relocation to industrial plants, bridges, and infrastructure sites prompted widespread concern that they were being used as human shields.

The U.S. government adopted a firm policy of refusing to negotiate over hostages, consistent with its broader anti-hostage doctrine shaped by earlier crises, including the Iran Hostage Crisis of 1979–1981. This stance severely constrained formal diplomatic options for securing releases.

By autumn 1990, conditions for detained civilians varied widely. Some were housed in hotels, others in government-controlled facilities. Although not uniformly subjected to physical abuse, their detention was coercive and involuntary. The uncertainty surrounding their fate became a prominent issue in Western media, contributing to public anxiety and political pressure.

While several governments pursued quiet diplomatic channels, progress was uneven. Iraq released some detainees selectively, often framing releases as acts of goodwill designed to influence international opinion rather than responses to diplomatic pressure.

By 1990, Muhammad Ali was no longer an active athlete but remained one of the most recognizable figures in the world. His historical significance extended well beyond boxing. Ali’s refusal to be drafted into the U.S. Army during the Vietnam War, his subsequent conviction (later overturned), and his public embrace of Islam had transformed him into a global symbol of dissent and moral independence.

In the Arab and Muslim worlds, Ali was widely respected as both a cultural figure and a religious convert who had publicly resisted Western military authority. This reputation distinguished him sharply from American political leaders and rendered him uniquely credible in contexts where U.S. diplomacy was viewed with suspicion.

At the same time, Ali’s health had deteriorated significantly. Parkinson’s disease had already impaired his speech and movement, making his decision to travel physically demanding and publicly visible.

Ali’s involvement did not originate from official U.S. government planning. Instead, it emerged through informal humanitarian intermediaries and contacts who believed his presence might succeed where traditional diplomacy had failed. Crucially, Ali did not travel as an emissary of the U.S. state, a distinction that allowed Iraqi authorities to receive him without appearing to yield to American pressure.

The mission was framed explicitly as humanitarian rather than political. This framing would later prove essential in allowing Iraq to present the detainees’ release as voluntary rather than coerced.

Ali arrived in Baghdad in late November 1990. On 27 November, he met with Saddam Hussein. Contemporary reporting suggests the meeting was conducted with considerable formality but avoided direct political bargaining. Ali’s appeal emphasized the civilian status of the detainees and the moral implications of their continued detention.

Ali’s rhetoric drew on shared religious language and ethical concepts rather than diplomatic leverage. By emphasizing compassion and honor, he offered Saddam Hussein a means of releasing detainees without undermining his public posture of resistance to Western demands.

Following the meeting, Iraqi authorities announced the release of fifteen American civilians. The decision was presented domestically and internationally as a gesture of goodwill rather than a concession. Ali accompanied the released individuals out of Iraq, personally escorting them back to the United States.

Photographs and television footage of Ali alongside the freed detainees circulated widely. These images quickly became the defining visual record of the episode, reinforcing Ali’s role in public memory.

The U.S. government publicly welcomed the return of the detainees while maintaining deliberate ambiguity regarding Ali’s role. Officials avoided framing the episode as a diplomatic breakthrough, emphasizing instead that U.S. policy toward Iraq remained unchanged.

This cautious response reflected concern that acknowledging success through informal channels might undermine official diplomatic doctrine or encourage future hostage-taking. Military preparations continued uninterrupted, and coalition strategy remained focused on the liberation of Kuwait by force if necessary.

In December 1990, Iraq released most remaining Western detainees, a move widely interpreted as an attempt to improve its international standing ahead of a looming military confrontation. These releases did not prevent the initiation of Operation Desert Storm in January 1991.

Ali’s mission thus occurred within a narrow historical window — after the invasion of Kuwait but before the transition from diplomatic pressure to armed conflict.

Muhammad Ali’s role in securing the release of fifteen American detainees in Iraq in 1990 occupies a modest but well-documented place in late twentieth-century history. It stands as an example of how historical circumstance, personal reputation, and humanitarian framing converged to produce a limited but meaningful outcome within an otherwise rigid geopolitical confrontation.

While the Gulf War proceeded unchanged, the episode remains historically significant as evidence that diplomacy, even during periods of intense international tension, could occasionally be shaped by actors operating outside formal structures of power.